Stranded at Sea during COVID-19 Restrictions

- Author(s):

- By Robert Hausen, Christian Rohleder, Julia Fruntke and Gertrud Nöth, all staff at Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD), supported by information taken from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) press release of 24 April 2020

The crew, staff and researchers on the RV Polarstern, a German research vessel, found themselves stranded aboard a ship drifting in the ice in the Arctic in March when COVID-19 restrictions made scheduled changes of staff virtually impossible. Two staff from Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD), Robert Hausen, a meteorologist, and Christian Rohleder, a weather technician, were aboard. This is their story.

|

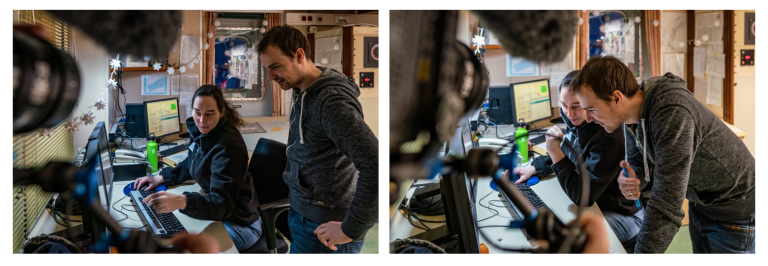

Robert Hausen (left) and Christian Rohleder (right) in front of RV Polarstern on 09 April (right photo). Picture-perfect weather after the storm: the two Twin Otters landed close to the Polarstern to pick up scientists who couldn’t stay longer for personal reasons on 22 April (left photo). |

Polarstern never leaves port without its shipboard DWD weather station, and that was the case on 5 November 2019 when the research icebreaker set-off from Tromsø, Norway. The MOSAiC expedition called for five exchanges of crew, scientists and DWD meteorological staff on an over 13 month journey.

“As a long-standing partner of the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), we are delighted to support this unique expedition from the meteorological side by seconding our experienced colleagues on board the ship,” said Prof. Dr Gerhard Adrian, President of the DWD, who is also the President of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). “The expedition will promote weather and climate research around the world by contributing valuable insights into physical processes in the Arctic, which are becoming increasingly important in the ongoing climate change.”

Fully packed daily routines

During MOSAiC expeditions, the RV Polarstern drifts with the ice in an area where data for weather forecasts are scarce. The data needed for onboard meteorological briefings reach the ship through very low bandwidth connections with polar-orbiting communication satellites. The shipboard weather station has a reception antenna to receive near real-time images from meteorological satellites in polar orbit. Moreover, data obtained from onboard radiosonde ascents are indispensable for the expedition’s weather forecasts.

|

|

Changeover in the weather station office: meteorologist Julia Wenzel (DWD) hands over control to Robert Hausen (02 March). |

The role of the onboard meteorologist is to provide the captain, cruise leader and helicopter crew with weather forecasts to ensure safe and efficient operation of the expedition. The weather technician is responsible for the station’s meteorological sensors and daily radiosonde launches and assists the onboard meteorologists with the collection, processing and preparation of meteorological data.

|

|

In the white-out of the Arctic: Robert Hausen (left) (10 March). |

“For the weather station staff, it means getting up early, every day, without exception,” reports Hausen. “Producing the morning reports, meeting with the captain, chief scientist and pilot, continuously monitoring the weather, viewing and interpreting the latest satellite and model data, providing meteorological advice for all activities on the ice, preparing the presentation for the evening meeting, updating the weather reports in the evening,” is his telegram-style description of the working day aboard the Polarstern. Hausen continues, “This can only be achieved thanks to the work of our weather technician on board, and thanks to the many colleagues back home at the DWD, who provide further data that help us to produce weather forecasts onboard all-day round, in particular for flying operations.”

Specifically, it is the aeronautical meteorological briefings for the crew of the on-board helicopter that take the most time and effort. They cover weather conditions for take-offs and landings as well as the conditions during flights over the ice. Key elements are cloud-base height, visibility and the risk of icing as well as the assessment of weather conditions regarding possible white-out situations – how well the helicopter pilot can see the horizon line during the flight and/or identify the topography of the snow surface.

|

Scientists in sea fog on the floe (23 March) (top right). Always present: a camera team from the German film and television production company UFA, here interviewing Robert Hausen (left) on the ice floe (23 March) (bottom right). Without meteorological advice, flights of the on-board helicopter, which busily transported equipment and measuring devices to the floe, would have been impossible (25 March) (right). |

The weather technician’s daily schedule is similarly packed. “The first task in the morning is to check that the meteorological sensors on board work properly. This means getting out of the weather station office up on deck in all wind and weather,” explains Rohleder. “The meteorologist then immediately needs the weather data for the morning briefing. Apart from the weather observations we take on board, we receive most of the data from the DWD’s offices in Offenbach or Hamburg. All observations must be transmitted regularly, every three hours. In addition, there are the radiosonde ascents, which are carried out four times a day and in special weather situations as often as eight times a day. It may even happen that we launch an additional weather balloon before a helicopter takes off in order to get a data update and keep the pilots informed about the weather during their flight. Later, I support the meteorologist again for the evening meeting, which reviews the past day’s weather but is mainly aimed at discussing what the weather will be like on the next day. And for that we need up-to-date data.”

The AWI Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research provides all the sensors on board RV Polarstern; however, maintenance, minor repairs or the replacement of defective sensors are the weather technician's job. Major repairs, especially on the ship’s mast, are carried out in co-operation with the electronic engineers on board.

Stranded on board

|

| Robert Hausen (sitting left in the front) with the helicopter team on the floe (09 April). |

Hausen and Rohleder were in the third of the five planned expedition legs. They set out from Tromsø aboard the Russian icebreaker Kapitan Dranitsyn on 27 January 2020 but took over four weeks to reach Polarstern. "Immediately after we put to sea, we encountered our first delay. Heavy storms raging in the Barents Sea forced us to wait in a fjord for about a week for better weather. After a short passage into open water, we set off on an arduous journey through often multi-year ice north of Franz Josef Land on 7 February. The distance to RV Polarstern, which was drifting a little north of 88 °North, was over 600 kilometres. On some days, the ice pressure acting on the ship was so great that we made only a few kilometres and we began to doubt if we would ever get there. We reached our final position for the exchange on 28 February – about two weeks later than planned," explained Hausen.

"We had just about settled in on the Polarstern when the COVID-19 pandemic took on an incredible dynamic with an ever-increasing number of infections, deaths and restrictions within a very short time," said Hausen. “Pictures of the deserted inner cities of Berlin, London, Rome, Madrid or New York, etc. seemed so surreal. I couldn’t believe it, had no idea what to think of it. Then we watched the speech by our Federal Chancellor Angela Merkel [on 18 March] here on board. Afterwards, several crisis meetings were convened during which option after option for staff rotations to replace those on board were ruled out – partly because our runway was insufficiently developed due to the dynamics of the ice, partly because of the stringent restrictions imposed due to the COVID-19 crisis. By the middle of March, it was clear to us that we would not be able to return in April and probably not in May either – if MOSAiC was going to be continued. At first, that was quite a shock!” The original plan was for team 3 to return to Germany on 5 April.

AWI Professor Torsten Kanzow, then cruise leader on the Polarstern, commented, “People with families tried, as much as possible, to stay in touch with their loved ones at home via satellite telephone and e-mail. As cruise leader, I collected the worries and concerns of the people on board and reported them to the project co-ordination team and the AWI. This way, we regained a bit of security in planning.”

Seven staff were finally flown out on 22 April – personal circumstances left them with no choice but to discontinue their work in the project. But that brought challenges for the DWD staff. "A week before the two Twin Otters were to fly out from Station Nord on Greenland, originally planned for 19 April, we supplied the pilots and the AWI logistics team with detailed, daily updated forecasts. In addition to our own data, we received TAFs [Terminal Aerodrome Forecasts] from Station Nord and sent them back METARs [METeorological Aerodrome Reports] and Polarstern Airfield Forecasts (PAFs),” said Hausen. “But instead of moving on as expected, a bad weather system persisted from one day to the next and from model run to model run. Two to three days before the 22nd, there were signs that the flight could eventually become possible on that day. But white-out conditions persisted until the eve of 22 April. Marking the runway on the ice floe at a length of more than 400 metres was only possible the very morning. The weather played along and so the two Twin Otters took off from Station Nord in Greenland, with which we were in constant contact, and landed close to the Polarstern a little more than two hours later."

|

| Portrait of Christian Rohleder (12 April). |

Research activities on the ice floe continued with great enthusiasm despite all the challenges and the participants’ concerns. From 25 March onward, the work was done in the endless sunlight of the Polar Day. Nearly the entire third team stayed and continued their tasks with undiminished devotion.

When the team members realized that they would probably be on board for two months longer, they reacted quite differently. "Some people on board were so totally absorbed in their daily scientific work even after such a long time that they’d rather not leave at all. Others would have liked to be back with their families today rather than tomorrow. My colleague Christian Rohleder and I continued our work as always, as a team and highly motivated. We had to accept the situation as it was, there was simply no alternative,” said Hausen. “Our physical well-being was well cared for and the food was varied and tasted great. After work, we had plenty of leisure opportunities, such as the fitness room or the sauna, or playing water polo, table tennis or table football.” But the situation did eventually get to them, “After a few months, we slowly started to feel physically and, above all, mentally exhausted. Moreover, we felt that the situation at home could change abruptly at any time. This was probably one of the most difficult things we had to cope with, that is learning to deal with uncertainty."

"We watched the daily COVID-19 updates in the news with great concern," said Rohleder. "No one could predict how the crisis would develop. The only thing we knew for sure was that we on board could not fall ill with COVID-19 – but what about our families back home? This question became a top priority for me on 31 March when my daughter told me via WhatsApp that she had the virus. As a nurse, she was at high risk from the very beginning, but now it was certain. During the next ten days or so, she struggled with the symptoms. Even after that, she repeatedly tested positive for the virus and, in the end, her quarantine lasted 45 days! You just feel helpless, so far away and nervously waiting for information from Bremerhaven on what was going to happen with the expedition.”

Alternative resupply plan: rendez-vous at sea off Spitsbergen

The Polarstern crew exchange between the third and fourth team of the expedition was originally planned to take place mainly by air. The idea was to build a runway on the ice floe where the Polarstern was docking. The aircraft for the transport of staff and material to and from the Polarstern were to take off and land in Longyearbyen on Spitsbergen. This plan, however, was thwarted by the COVID-19 pandemic and by the dynamics of the ice floe. Finally, new, alternative resupply plans, developed with the support of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the partners of the German Research Fleet, as well as the dedicated work of MOSAiC team three made it possible to continue the expedition into its next phase.

In the end, the changeover took place at sea with the German research vessels Sonne and Maria S. Merian. Both ships had returned to Germany shortly before because of the restrictions imposed to mitigate the pandemic, so they departed together from Bremerhaven. RV Polarstern left the ice floe in mid-May to meet the Sonne and Maria S. Merian in calm waters off Spitsbergen at the end of May. "But again, the plan was shaken up when we had to fight through compact multi-year ice and only rarely found larger ice-free areas. The exchange, about 100 people altogether, and the reprovision of freight and supplies, finally took place in the Isfjord near Longyearbyen," reported Hausen. The RV Polarstern then returned to the ice floe to continue its Arctic expedition. Several measuring instruments had been left on the ice so observations could continue autonomously when Polarstern veered south for the exchange, but others had been dismantled and had to be put back into the ice.

Extensive safety guidelines, prepared in close co-ordination with the German and Norwegian health authorities, had made the resupply and exchange possible. The fourth expedition team underwent controlled quarantine measures for 14 days in Germany before their departure and were tested repeatedly for the coronavirus during that time.

It was then decided that there would be only one further exchange of staff because of the delay in this exchange. Irrespective of this, the expedition ended in mid-October as scheduled.

|

|

The Polarstern received occasional visits from polar bears (left). Shortly before leaving for Spitsbergen: equipment is collected from the floe and hoisted aboard. Next to the railing, you can see one of the two weather screens, both of which belong to the DWD as part of the weather station’s equipment (14 May). |

Finally home

Team three was finally on their way back home. After a somewhat rough crossing to the coast of Norway, the passage got calmer. "At first, doing nothing was a great pleasure, but then the only wish was to get home," added Hausen. The entire team arrived safely in Bremerhaven on 15 June. From there, they returned directly home to their families.

When Rohleder arrived in Bremerhaven, his primary wish was a smooth journey home by train. "It was so strange and unfamiliar to see people with mouth and nose protections on the street or to sit behind a protective partition in the taxi to the train station," he reported. Robert Hausen shared the same impressions, before concluding, “My family picked me up at the station. To finally see them again after five months was an overwhelming feeling for me. But what remains in the end is the memory of an exciting, unforgettable time that had its ups and downs, but with the positive aspects prevailing clearly. Once you have got to know and love the Polar regions, you will be fascinated forever.”

About the persons:

Robert Hausen, graduate meteorologist, employed at the DWD since 1 November 2009. He worked twice at Neumayer Station in Antarctica as a forecasting meteorologist for the DROnning Maud Land Air Network (DROMLAN). He also served as an on-board meteorologist on the German research vessels Meteor and Polarstern.

Christian Rohleder, weather technician, has been working at the DWD for 33 years. Until 1990, he was a member of the Meteorological Service (MD) of the former German Democratic Republic, which was integrated into the DWD in the course of Germany’s reunification. He took part in numerous missions on the research vessels Meteor and Polarstern.