Communicating for Life-saving Action: Enhancing messaging in Early Warnings Systems

- Author(s):

- Eliot Christian, Carolina Cerrudo, Elizabeth Viljoen, Nathan Cooper, Ronald Jackson, Vanessa Gray and Adanna Robertson-Quimby

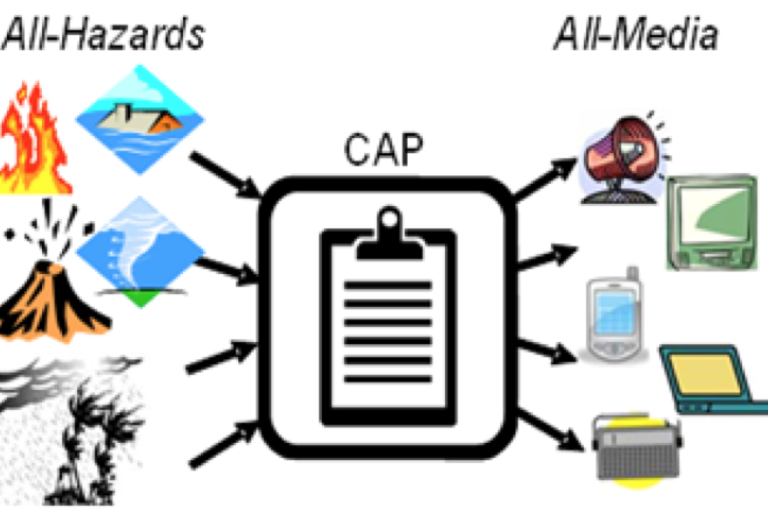

Hazards can be natural or technological (or man-made), and multi-hazard conditions are common. When hazards cascade, they can lead to a large-scale disaster. For example, a severe rainstorm can cause flooding, which may contaminate water sources, which in turn may precipitate a cholera outbreak. Disaster risk can be viewed as a function of multiple factors, including hazard, exposure, vulnerability and capacity building. To mitigate risks and avoid hazards cascading into disaster, early warning system (EWS) require partnerships, enabling environments, enhanced communication, capacity building and effective messaging using all available media (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Integrated Early Warning System (Source: ITU) Figure 1. Integrated Early Warning System (Source: ITU) |

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030) calls for nations to substantially increase the availability of and access to multi-hazard early warning systems (MHEWSs), disaster risk information and assessments for the public, emergency services providers and market sectors. EWSs seek to provide timely and actionable information to the public as well as to others involved in the emergency. EWS, also known as Emergency Alerting Systems, help people to take action to save lives and livelihoods in emergency situations, and thereby avoid situations escalating into disasters.

Strong growth in information and communication technology networks and services is increasing the number of communication platforms and channels and bringing new opportunities to reach communities at risk. Before and during emergencies, EWSs can include: hazard threat monitoring, forecasting and prediction, risk assessment, communication and other activities that enable individuals, communities, governments, businesses and others to take timely actions that protect lives and livelihoods. It therefore requires experts in many roles pulling together and a sound understanding of threats, the environment and the users of information.

WMO promotes two widespread practices that strengthen EWSs with an emphasis on improving messaging for action:

- The international standard Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) for communicating the key facts for any kind of emergency over all available media.

- Impact-based Forecasting and Warning Services (IBFWS), that is to say public messaging focused on the exposure and vulnerability of people in harm's way.

CAP and IBFWS are complementary and are often used in combination.

Common Alerting Protocol (CAP)

The international standard CAP (ITU-T Recommendation X.1303) provides a format for communicating the key facts for all kinds of hazards across all media:

- What is the emergency?

- Where is the affected area?

- How soon should people act?

- How bad will it be?

- How certain are the experts?

- What should people do?

Key facts of a CAP message

Figure 2. CAP as a clipboard with a standard business form that contains basic relevant information for everyone involved in the emergency. Figure 2. CAP as a clipboard with a standard business form that contains basic relevant information for everyone involved in the emergency. |

Multiple authorities with distinct responsibilities are often involved in complex emergencies. For example, scientific and technical agencies are experts at characterizing a hazard and its potential impacts, but are not usually empowered to instruct people on actions such as evacuation. Their CAP alerts might instruct people to "Monitor local media for instructions from your civic authorities." The CAP alert from a civic authority can use the emergency description provided by the scientific and technical agency and add instructions such as evacuation routes. (The WMO Education and Learning Moodle site also offers a self-study course on CAP.)

When an emergency is extensive, it is common to have overlapping jurisdictions, and different authorities might issue more alerts as the emergency evolves. Use of CAP by all alerting authorities to communicate key facts as the emergency unfolds helps ensure coherent messaging (Figure 2). This applies to private communications among alerting authorities and affiliates as well as to public messaging.

As most emergencies are small-scale and occur often, people become familiar with routine local alerting systems such as the weather alerts. In contrast, disasters are always larger scale and much less frequent. Ideally, these routine alerting systems should be able to scale up to handle disaster early warnings. People would then be alerted to a pending disaster situation through the same system they know and trust.

Benefits of CAP – Traditionally, societies everywhere had a patchwork of alerting systems, often designed just for particular emergencies and specific communications media. A patchwork approach is not only wasteful but may also be dangerous if:

- People miss out on alerts they should have received.

- People receive alerts that are not intended for them.

- People receive confusing messages that are difficult to confirm.

CAP works for all types of emergencies and media because messages are a mixture of information and data. They contain text information that people can read, such as a headline, event, instruction and area description, and data that are crucial for automated processing such as the area polygon and coded values.

CAP makes it quicker and easier to issue alerts. Authorities can issue alerts by making phone calls, sending e-mails and posting to online media, among others, but such activities consume valuable time, distracting from the mission of composing accurate and actionable alerts. With CAP, a single message disseminates quickly over multiple alerting channels. CAP is the fastest and the least error-prone way to disseminate emergency alerts to people in harm’s way.

In a complex emergency, many types of information from many sources have to be assimilated at all scales. Alerts are a big part of that. Without CAP, alerts are difficult to get, use and share, because they are communicated in so many media and formats. Information gathering and analysis is much easier with CAP alerts, helping support "Shared Situational Awareness" or maintaining a "Common Operating Picture."

Many people in harm's way – for example, the blind, deaf, cognitively impaired or those who do not understand the language used in the alert – are underserved by traditional public alerting systems. The data features of CAP can be exploited to address all of these audiences, and includes automated translation.

Some hazards occur so suddenly that seconds can mean the difference between timely, life-saving alerts and alerts that arrive too late, for examples: earthquakes, tornadoes, tsunami, flash floods, volcanoes, landslides and avalanches. CAP alerts can be posted immediately through an online facility that immediately disseminates to many media.

CAP messages are digital, enabling immediate action by people and devices, such as sirens, highway signs, train controls and other automated mechanisms, that help save lives. For example, CAP was used by the National Emergency Management Organisation of Saint Vincent in April 2021 to issue a public alert for a volcanic eruption.

CAP alert for the 2021 volcanic eruption in Saint Vincent Volcano

Although 85% of the world’s population live in countries that are using CAP, uptake of CAP has been weakest among developing countries and especially the 46 Least Developed Countries (LDCs), even though those are the most vulnerable to disaster (Christian, 2022). This is why international organizations, international NGOs, and multi-national companies involved in emergency alerting are urged to endorse the Call to Action on Emergency Alerting:

To scale up efforts to ensure that by 2025 all countries have the capability for effective, authoritative emergency alerting that leverages the Common Alerting Protocol (CAP), suitable for all media and all hazards.

Knowing the Authoritative Sources – CAP is very useful for communicating key facts, but it is essential to know those facts are right. Given that alerting relies on large networks like the Internet, it is not possible to know all of the sources personally. How can people know which alerting sources are officially recognized as authoritative? The international Register of Alerting Authorities was set up in 2009 by WMO and ITU for that purpose. The Register is somewhat like a referral service – you have a degree of trust in a registered alerting authority because you trust the institutions that registered them. Each WMO Permanent Representative (PR) maintains entries for their nation. The PR represents the entire nation and should register all nationally recognized alerting authorities.

CAP Alert Hubs – A CAP Alert Hub provides simplified access to aggregated CAP alerts. This is necessary given the many thousands of CAP alert news feeds now operating. The alerts can be aggregated around any theme, any time frame, or any geospatial scale: city, province, nation, region or global.

CAP HubsAt a national scale, the United States Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS) is a CAP Alert Hub aggregating alerts from more than 1 600 alerting authorities. At a regional scale, MeteoAlarm aggregates alerts from 37 National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) in Europe. At the global scale:

|

Impact-based Forecasting and Warning Services

Figure 3. Risk expressed as the probability and magnitude of harm attendant on human beings and their livelihoods and assets because of their exposure and vulnerability to a hazard. (Source: WMO-No. 1150) Figure 3. Risk expressed as the probability and magnitude of harm attendant on human beings and their livelihoods and assets because of their exposure and vulnerability to a hazard. (Source: WMO-No. 1150) |

Impact-based forecasting is a structured approach for combining hazard related information with exposure and vulnerability data to identify risk and support decision-making (Figure 3). Its ultimate objective is to encourage early action that reduces damages and loss of life from natural hazards by providing information about the hazard, about the potential impacts it may cause and recommended actions to minimize the effects of these impacts for society (UNESCAP, 2021 and WMO 2021).

The introduction of the concept of risk in weather forecast represents a paradigm shift from providing information on “what the weather will be” to “what the weather will do”. The WMO Guidelines on Multi-hazard Impact-based Forecast and Warning Services, Part II: Putting Multi-Hazard IBFWS in Practice (WMO-No. 1150) focuses on partnerships, training, communication, the value of IBFWS and impact information and methodologies for analysis. Here the focus is on some of the considerations in the Guidelines’ chapters on partnerships and communication, however, the importance of the availability of impact, exposure and vulnerability data for achieving this change of paradigm in weather forecast services cannot be understated.

Many players have a crucial role in emergency management: governments, international institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), humanitarian aid agencies, volunteer organizations, community initiatives and numerous others at local, national, regional and international levels. Depending on the scale of the emergency, multiple levels of government are likely to be involved in emergency management functions in a monitoring role if not operationally. Governmental authorities can include the agency responsible for coordinating the government’s response, the telecommunications regulatory authority, scientific or technical agencies with expertise in the particular natural or technological hazard that is threatening, and responder agencies such as police, firefighters, civil protection and health workers. For a disaster situation at the national or cross-border level, the Head of the Government and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs would also be involved. Many national institutions with a key role in emergency management have intergovernmental counterparts in the United Nations system that can lend assistance, especially with regard to trans-border issues and coordination.

One of the key factors of an effective IBFWS is thus the building of partnerships with this broad range of key players. The aim of such partnerships is to improve the overall response to hazards and avoid disaster situations and other adverse outcomes. Enhanced, substantial engagement between meteorological service providers and decision-makers is required with roles and responsibilities defined as clearly as possible, and resources provided to ensure ongoing and sustainable engagement.

Collaboration among the alliance of actors in the delivery of services will be key to ensure that efforts are adequately resourced, sustainable, harmonized and deliver real impact. In the Caribbean, for example, efforts have been advanced to establish a coordinating mechanism aimed at identifying and defining a vision, agreeing on areas of priorities, and harmonizing programmes and project investments. Among the key EWS actors are scientists, technocrats, policymakers and users, as well as international, local and private sector organizations.

Training is an important part of IBFWS and its partnerships. IBFWS requires an understanding of information that is not covered during the formal training of meteorology and therefore there is a need to develop competencies within the NMHSs and partner organizations. For IBFWS to progress, NMHSs and partner organizations must provide the means to develop the required skill sets and competencies, as well as knowledge of how partners mutually use information to deliver on their mandates.

Once the essential and strategic partnerships are in place and the necessary information gathered, this information needs to be effectively communicated.

Excellence in communication is necessary for effective transfer of information, knowledge and experience between partners. Good communication practices build trust. Many countries make use of advisors with a good background understanding in meteorology to bridge communication gaps and act as links between the NMHS and its partners.

The risks associated with a hazard also need to be communicated for appropriate actions to be taken. IBFWS are about driving effective actions, and clear, understandable communication of potential risks is an essential element in achieving this. Risk communication is closely bound up with the communication of probability. For persons to take appropriate actions in response to a hazard, they must be able to form an accurate perception of the risks – to themselves if they are individuals, or, if they are agencies, to protect the communities, facilities or infrastructure for which they are responsible. IBFWS provide an overview of the concepts of awareness and reach, and describes a structured approach to considering what level of information should be matched with each communication medium (Figure 4).

|

Figure 4. A marketing “Reach Model” can be used to show the steps to be implemented for risk communication for forecasts and warnings:

- Awareness and reach for understanding users’ needs and access to, risk advice

- Trust making sure users trust this advice

- Understanding ensuring users accurately perceive their risks and know how the advice applies to them

- Action enabling users to take the right actions on the timescales they need

|

Broadcasters and other media play a crucial role in disseminating relevant information before, during and after disasters. These include wireless and fixed service providers, as well as satellite providers, public safety radio networks, TV and radio broadcasters, and Internet service providers, among others. Today, more than 60% (4.9 billion people) of the world’s population are using the Internet (ITU, 2021). This has given rise to many new emergency alerting services, including mobile apps, or app-based alerting system. IBFWSs, in turn, need agility to evolve at correspondent speed to include social media as well as other emerging communication technologies to issue messages that are clear and consistent.

Figure 5. The IFRC's Public awareness and public education for disaster risk reduction: key messages offers a field tested set of globally relevant messages for different hazard types and alert levels Figure 5. The IFRC's Public awareness and public education for disaster risk reduction: key messages offers a field tested set of globally relevant messages for different hazard types and alert levels |

Research shows that people often find emergency alert messages confusing. Sometimes messages are understood but the phrasing does not prompt actions. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Public awareness and public education for disaster risk reduction: key messages offers a field tested set of globally relevant messages for different hazard types and alert levels (Figure 5). Messages can be adapted and harmonized by national governments and civil society organizations, leading to a common, agreed upon set of messages that can be transmitted in tandem with hazard warnings. This helps to ensure that people in a given country receive the same information about what actions to take to stay safe no matter what the source. PAPE messages are based on case studies where individuals at risk received and understood emergency messages then took the actions prompted.

The Internet, social networks, cellular operators and smart apps can communicate certain kinds of information and official alerts to help keep people informed. Warning systems based on sirens or public address systems connected to sensors can be useful to quickly trigger an alert in certain settings when a set threshold is reached. Satellite networks provide communications services that have very little dependence on terrestrial infrastructure. Private telecommunication services include networks serving firefighters, police, ambulances, relief teams, civil protection, transport, and utilities as well as other public and private sector entities.

The ITU estimated that by the end of 2021, 95% of the world’s population would have access to a mobile broadband network. Active mobile broadband subscriptions worldwide reached more than 6 billion in 2021. Mobile services have become an essential part of most people’s lives. A growing number of countries are taking advantage of cellular networks and technologies to send alerting messages, including location-based technologies, such as Short Message Service (SMS) or Cell Broadcast (CB). Some are putting specific regulations in place. As telecommunication networks, services and platforms grow, they are shaping the way people acquire information and playing an increasingly important role in EWSs by offering more options for delivering timely alerting messages to those at risk. For example, sending the same CAP alert message over multiple platforms increases coverage and impact, and minimizes confusion. CAP offers the best solution for communicating to all of these audiences – public, private, commercial – in any emergency situation (Figure 6).

Figure 6. CAP alert by itself does not include everything about the emergency, it just carries some facts that everyone needs. (Source: ITU) Figure 6. CAP alert by itself does not include everything about the emergency, it just carries some facts that everyone needs. (Source: ITU) |

Demonstrating the value of IBFWS

Numerous methods exist for the collection of weather information, however, there is no global standard for the collection of impact data, which make it difficult to demonstrate the value of IBFWS. However, impact information can be collected from various sources, including government ministries, newspapers and universities.

The socioeconomic benefits of IBFWS need to be validated by collecting and analysing case studies that can demonstrate their value to key decision-makers in government and other sectors as well as current and potential partners. There is no one measure of the value of IBFWSs, but there are three broad categories for measuring such value: timeliness, relevance and outcomes. Some examples of how value can be measured are provided in Chapter 5 of the afore mentioned WMO Guidelines. It is important to measure the value as this can enhance products and services.

Creating enabling environments

National legislation, rules and regulations are very important to create an enabling environment for emergency management. These can define the responsibilities of those who play a role in emergency management and determine coordination mechanisms. One national-level planning document that is especially relevant to EWS is the National Emergency Telecommunications Plan (NETP). An NETP sets out a strategy to ensure communications availability during all phases of the disaster, by promoting coordination across all levels of government, between public and private organizations, and within communities at risk. Some countries have also passed specific regulations to ensure that communities at risk benefit from digital platforms and communication channels. For example, the European Electronic Communications Code Article 110(1) stipulates that by 21 June 2022:

- Public warning system must be able to send geo-targeted emergency alerts. (Official Journal of the European Union, 2018)

- The public alerting system must be able to operate without an opt-in requirement. (Official Journal of the European Union, 2018)

- They must be accurate enough to reach a very high percentage of people quickly, including visitors in their native languages. (Official Journal of the European Union, 2018)

A lot remains to be done

For all kinds of hazards and across all media, the international standard CAP provides a format for communicating the key facts about an emergency. IBFWS offer a structured approach for combining hazard related information with exposure and vulnerability data to identify risk and support decision-making, with the ultimate objective of encouraging early action that reduces damages and loss of life from natural hazards. As complementary practices, the benefits of using CAP and IBFWS to enhance EWSs are very evident. Even though much progress has been made globally to advance these practices, there still remains a lot to be done.

A 2018 WMO commissioned3 evidence-based assessment of EWSs during the 2017 Caribbean hurricane suggests that losses of lives, livelihoods and assets are still excessive. It goes further to indicate that “with climate change and rapid development along coastlines, strengthening capacity to issue multi-hazard early warning that lead to effective response by institutions and people remains a priority….”

The Sendai Framework advocates EWS that empower individuals and communities threatened by hazards to act in sufficient time and in an appropriate manner to reduce the possibility of personal injury, loss of life and damage to property and the environment. In pursuit of the Sendai Framework’s 2030 goals, CAP and IBFWS, enabling environments, enhanced collaboration and partnerships and communication are integral parts of more effective disaster risk reduction efforts.

Authors

Eliot Christian (Consultant), Carolina Cerrudo, Argentina National Meteorological Service (SNM), Elizabeth Viljoen, South African Weather Service (SAWS), Nathan Cooper, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), Ronald Jackson, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Vanessa Gray, International Telecommunication Union (ITU), and Adanna Robertson-Quimby, WMO Secretariat

References

Christian, E., 2022: CAP Implementations Status Report.

International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2021: Internet, Use, Facts and Figures.

Official Journal of the European Union, 2018: Directive 2018/1972 of the European Parliament and of the Council, 15 December.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP)/World Meteorological Organization (WMO), 2021: Manual for Operationalizing Impact-based Forecasting and Warning Services (IBFWS), Thailand.

WMO, 2021: WMO Guidelines on Multi-hazard Impact-based Forecast and Warning Services, Part II: Putting Multi-Hazard IBFWS into Practice (WMO-No. 1150). Geneva.

WMO, 2015: WMO Guidelines on Multi-hazard Impact-based Forecast and Warning Services (WMO-No. 1150). Geneva.